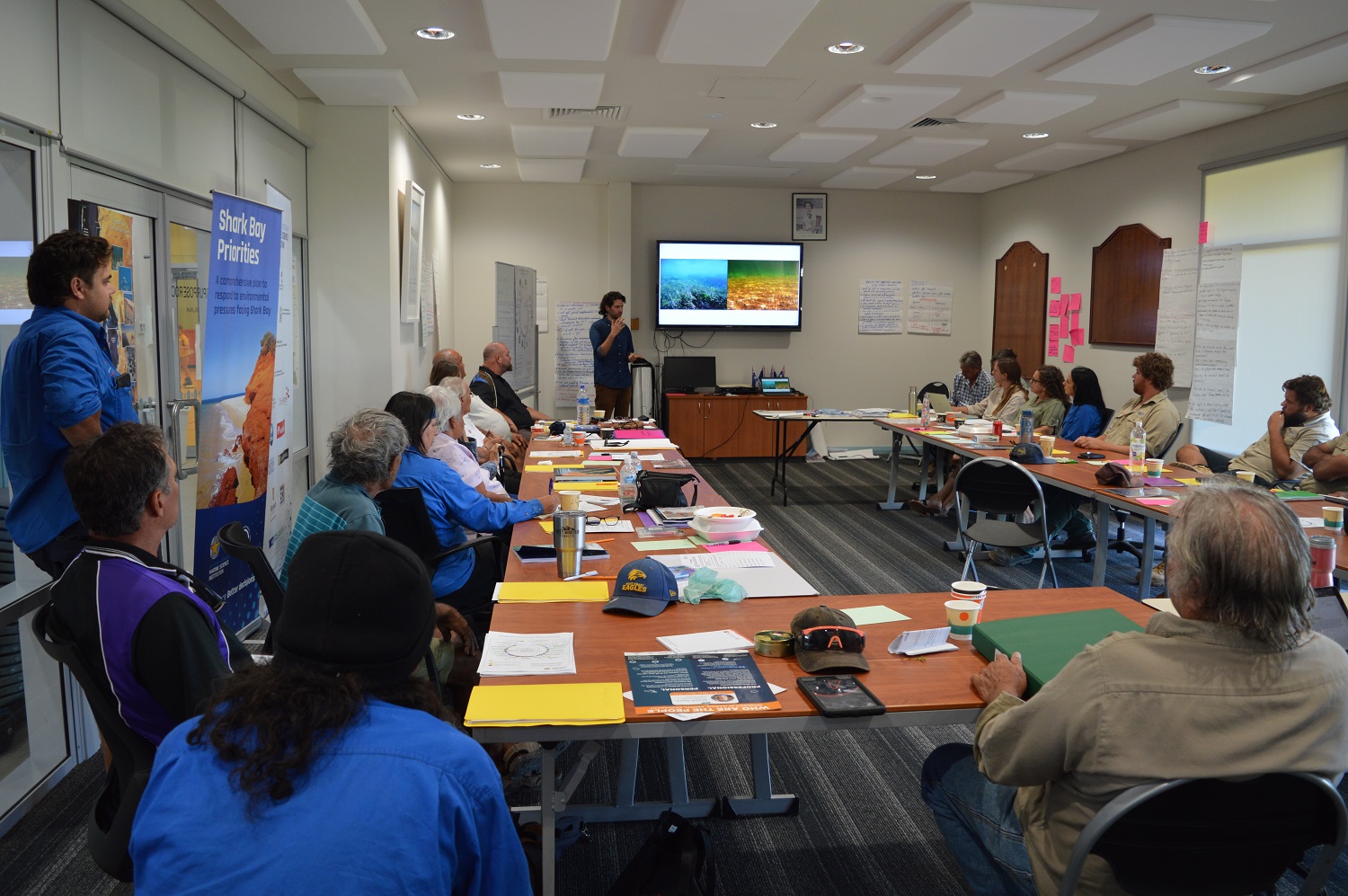

Encrusting sponge found in Kimberley coral reefs

The coral-killing sponge Terpios hoshinota has been detected in the Kimberley for the first time by scientists from the Western Australian Museum.

Terpios hoshinota is commonly referred to as ‘black disease’ because of its colour and because it overgrows both live and dead coral. It has been reported in many areas of the Indo-Pacific, including the Great Barrier Reef, but has not previously been found in Western Australian waters.

The sponge was detected during fieldwork in 2016 by the WA Museum’s Dr Jane Fromont, Dr Zoe Richards and Dr Nerida Wilson, with assistance from the Wunambal Gaambera Aboriginal Corporation and the Uunguu Rangers. Their research has now been published on open access scientific journal platform MDPI.

Dr Fromont said the Kimberley region of the State has some of the least impacted coral reefs globally.

“We report for the first time the presence of Terpios hoshinota in the eastern Indian Ocean on Kimberley inshore coral reefs,” Dr Fromont said.

“It is important to note that while there has been no outbreak event by Terpios hoshinota in the Kimberley, our observations of its presence suggest monitoring may be required to reduce the possibility of it spreading undetected. Terpios hoshinota is visually striking, and we encourage regional management authorities to include it in their reef health surveys.”

Dr Fromont said while the causes of Terpios hoshinota overgrowing corals remain unclear, the ability of the species to spread over coral reefs and cause coral death is concerning.

Where possible, small fragments of gray-black coral-encrusting sponge should be collected for expert identification at the WA Museum.

A copy of the research paper can be found at https://www.mdpi.com/1424-2818/11/10/184

Photo courtesy Dr Zoe Richards.