Temperatures soaring in surface and deeper water causing fish kills and coral bleaching

Elevated sea temperatures that have caused fish kills and coral bleaching along Western Australia’s coast, have been detected as far deep as 300 metres in some areas.

The Western Australian Marine Science Institution (WAMSI) is managing the ‘Advancing predictions of WA marine heatwaves and impacts on marine ecosystems’ project which aims to better predict and manage marine heatwaves. It is primarily funded by the Department of Jobs, Tourism, Science and Innovation in WA.

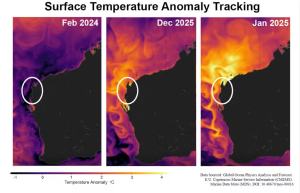

Dr Jessica Benthuysen, an oceanographer from the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS), who is one of the scientists working on the project, said the marine heatwave extended across much of the northwest.

“The temperatures reached unprecedented levels through December and January.” Dr Benthuysen .

“In mid to late January we saw warm waters exceeding three degrees above normal along the shelf from the southern Pilbara to Ningaloo and Shark Bay.”

“Monitoring shows the warm temperatures are not confined to just surface waters and have reached to at least 300 metres in the past few months, which has helped the extreme event to remain for such an extended period,” she said.

While southerly winds had provided some recent relief at Ningaloo, Dr Benthuysen said extremely warm waters had brought an early heat shock to underwater ecosystems well above the temperatures they would typically experience in March or April when waters tend to be warmest.

“With our partners we will continue to monitor temperatures along the coast with the help of the AIMS weather station at Ningaloo, eight coastal buoys deployed through this project, and Integrated Marine Observing System (IMOS) moorings and gliders.”

The equipment is being used to gather information for the heatwave project and feedback vital data to WAMSI’s partners about the current event.

WAMSI CEO Dr Luke Twomey said the marine heatwave project was an important one given the damage caused by marine heatwaves.

“For this project, WAMSI has brought together experts from across our partnership and beyond and also across various specialties” – Dr Twomey.

AIMS research scientist Dr James Gilmour said a collaborative approach was helpful to assess the full impact.

“We are working with our networks across management, research, Traditional Owner groups and other stakeholders to gather information on the bleaching but it will be some time before outcomes for WA reefs are understood,” Dr Gilmour said.

“Corals can recover from bleaching or they can also die – this process can take time and there are many variables influencing the outcome.”

“We will work with partners to interpret monitoring data from the many remote reefs in the vast expanse of the northwest,” he said.

Project scientists come from organisations including Bureau of Meteorology, Curtin University, Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions, Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development, Edith Cowan University, Murdoch University and The University of Western Australia.

Data from the smart moorings, including wave and temperature information, is publicly available at: www.wawaves.org

Photos by Dr Chris Fulton from the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) in collaboration with the Department of Biodiversity Conservation and Attractions (DBCA).