A powerful force is stopping the Indian Ocean from cooling itself – spelling more danger for Ningaloo

Widespread coral bleaching at Ningaloo Reef off Western Australia’s coast has deeply alarmed scientists and conservationists.

Photos captured by divers, published by The Guardian last week, show severe bleaching at several sites along the reef, which runs for 260 kilometres off the state’s northwest.

A severe marine heatwave in the Indian Ocean off WA has caused the coral bleaching. In some places, surface temperatures up to 4°C warmer than usual have been recorded.

Hotter temperatures aren’t only happening at the ocean’s surface – data indicates they also extend several hundred metres deep. Warm, deeper water can shut down the ocean’s natural cooling process, putting corals at even greater risk of bleaching.

Counting the cost

Scientists will conduct field surveys in coming months.

The full extent of damage to Ningaloo won’t be known until scientists conduct field surveys in coming months.

So far, bleaching has been documented at several sites, including Turquoise Bay, Coral Bay, Tantabiddi, and Bundegi (Exmouth Gulf).

Other sites such as Scott Reef, Ashmore Reef, the Rowley Shoals and Rottnest Island are also at risk.

Damage wrought by the heatwave extends beyond coral. More than 30,000 fish have died since the September onset.

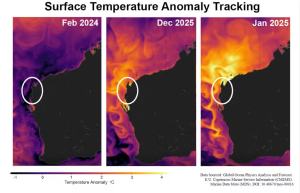

The below images show the heatwave’s progression. Temperatures from February last year are included for comparison.

The white circle shows the location of Ningaloo. Cooler temperatures are in blue and purple. Warmer temperatures are in yellow and orange.

The images show the heatwave reached Ningaloo in December last year and moved south in January. Temperatures fell slightly in February due to strong southerly winds. From March, temperatures are forecast to increase again.

Image showing the progression of an ocean heatwave down the WA coast. Ningaloo is marked by the white circle. CMEMS

A complex warming picture

According to recent data and modelled forecasts, hotter ocean temperatures off northern WA run several hundred metres deep.

This has been caused by developing La Nina conditions. La Nina and its opposite, El Nino, influence ocean temperatures and weather patterns across the Pacific.

During La Nina, trade winds strengthen and push warm water westward. This intensifies two important ocean currents.

The first is the Indonesian Throughflow – which carries warm Pacific waters through the Indonesian seas and into the eastern Indian Ocean. The second is the Leeuwin Current, which picks up this warm water and takes it further south towards Perth.

This has led to a build-up of hotter water along the WA coastline.

La Nina is also affecting WA’s reefs in other ways.

Some coral reefs are naturally cooled by local tides which pull deep, colder water towards the surface. This process, which has been likened to an ocean’s “air conditioner”, can temporarily relieve heat stress for reefs.

The process relies on “stratification” – that is, layers of seawater that differ in temperature, salinity and density (or weight). Warmer, less dense water collects at the surface and colder, denser water falls to deeper levels.

La Nina conditions can suppress, or even shut down, this cooling effect in two ways.

First, it reduces the difference in density between ocean layers. This causes water to draw upwards from shallower depths. Second, it increases water temperatures at depth.

All this means the water pumped to the surface isn’t much cooler than temperatures at the surface.

For many reefs along the coast of WA, the suppression of this tidal cooling is probably contributing to worsening conditions, and more coral bleaching.

Most bleaching forecasts rely on sea surface temperatures. This means scientists may be underestimating the vulnerability of deeper reefs.

What’s in store for Ningaloo and surrounds?

Looking ahead, the situation at Ningaloo and surrounding reefs remains critical.

Bleached reefs are able to recover if temperatures cool quickly. This means theoretically, Ningaloo and other affected reefs may survive the summer.

But unfortunately, temperatures are rising again and the marine heatwave is expected to continue until April, as the below image shows.

Climate change is making marine heatwaves more intense and frequent. It means reefs often don’t have time to recover between destructive bleaching events.

All this is compounded by the general trend towards warmer oceans as the planet heats up.

Drastic action on climate change is needed now. If this alarming pattern continues, the world’s reefs risk being lost entirely.

The project,

This article by Kelly Boden-Hawes and Professor Nicole Jones from The University of Western Australia, was originally published in The Conversation on 24 February 2025.

WAMSI is leading the project ‘Advancing predictions of Western Australian marine heatwaves and impacts on marine ecosystems’ which brings together scientists from around Australia who are developing improved knowledge and practical tools to forecast extreme ocean temperatures and their impacts on Western Australia’s (WA’s) marine ecosystems.