Adapting to ecosystem change in the Shark Bay World Heritage Site

Five years after a report into the Shark Bay World Heritage site recommended a coordinated collaborative approach was vital to understand changes in the ecosystem, more than 70 science and industry experts have joined forces to examine the threats and prioritise the research needed to save its status.

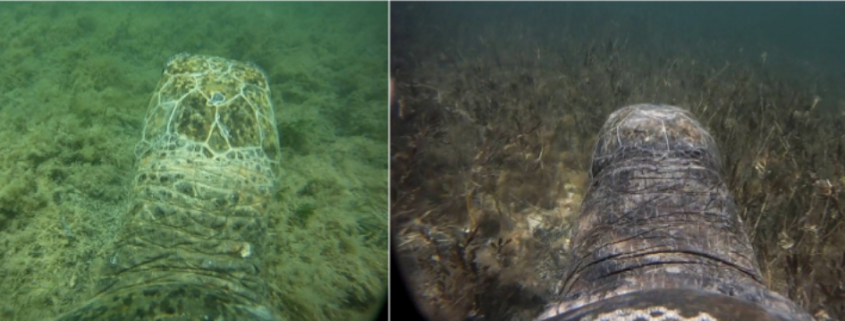

Shark Bay, located midway along the coast of Western Australia, occupies about 2.2 million hectares of marine and terrestrial reserves, featuring more than 30 islands, the largest (4,800 km2) and richest segrass beds in the world, five species of endangered mammals, as well as stromatolites. It is one of only 30 places on the World Heritage List of 1073, to satisfy all four natural criteria including:

To contain the most important and significant natural habitats for in-situ conservation of biological diversity, including those containing threatened species of outstanding universal value from the point of view of science or conservation.

A federal Governmnent report in 2009 titled the Implications of climate change for Australia’s World Heritage properties: a preliminary assessment, highlighted the uncertainties for Shark Bay created by the effect of climate change on the Leeuwin Current. Among its predictions was that increased sea temperatures could see tropical marine life move south and a greater likelihood of predation in the area by tiger sharks.

A marine heatwave in 2011 is now know to have caused a 20 per cent loss of seagrass habitat, equivalent to a loss of 1,000 km2 of meadows. Birth rates in dolphins dropped; crab, oyster and other fisheries were negatively affected. All this, while projected tourism numbers are fell well short of their mark.

In response, a workshop and resulting publication, focused on Shark Bay, recommended a coordinated multi-institutional and multi-discipline approach to research (Kendrick et al. 2012). However, five years on there is little evidence of such a coordinated approach to research.

This month, Professor Gary Kendrick from The University of Western Australia made another call to turn attention toward the potential demise of the unique World Heritage area and the response by more than 70 state, national and international experts was immediate.

“Given the changes that have already occurred and the scale of predicted further changes, a better understanding of the drivers of environmental changes on productivity is a critical step in being able to predict the ecological resilience of Shark Bay,” Professor Kendrick said. “We need to adopt appropriate management strategies to minimise the impacts of environmental variations on natural resources and the industries that depend on them.”

The expert workshop identified priority knowledge gaps and whether something could be done to address them. It assessed the importance of each gap by comparing the consequences of either ‘taking action’ to ‘doing nothing’.

|

| More than 70 Shark Bay science, industry and community stakeholders break into groups to come up with science priorities. (WAMSI) |

“It was a great day of brainstorming,” Professor Kendrick said. “Overall, there was consensus on concern over the ecosystem changes in Shark Bay but there was no consensus on how to resolve it.”

Professor Kendrick is now working to collate the workshop responses and identify the top science priorities in a white paper to the state government.

|

| The expert workshop ‘Adapting to ecosystem change in the Shark Bay World Heritage site’ identified concern over ecosystem change but no consensus on how to resolve it. UWA Professor Gary Kendrick will now identify the top priorities for science in a white paper. (WAMSI) |

Workshop presentations slides are available HERE