Seagrass put to test to find best species for withstanding climate change impact

Researchers looking at the possible impact of climate change on seagrass have tested the tolerance of the plants to rising temperatures after collecting samples at locations spanning 600 kilometres.

Nicole Said, a research associate from Edith Cowan University who is part of the WAMSI Westport Marine Science Program project, said six seagrass species were collected within Cockburn Sound and one, Posidonia sinuosa was collected along Western Australia’s coast from Geraldton to Geographe Bay.

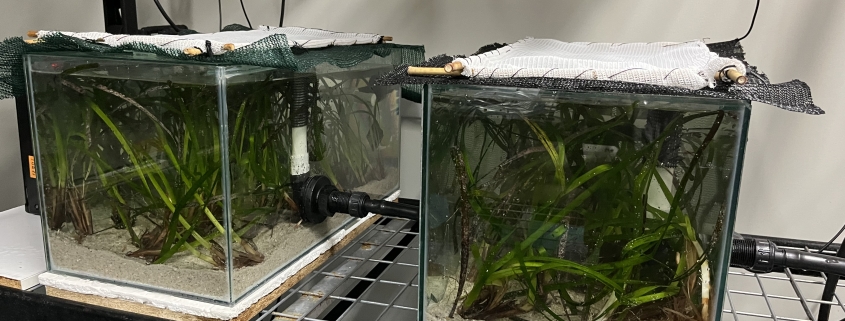

The samples, which represent species that are all found in Cockburn Sound, were then put in chambers and subjected to incremental increases in water temperature from 15 to 43 degrees over 12-hours.

Oxygen changes in the water were measured to calculate the plant’s photosynthetic rate or the rate at which light energy was converted into chemical energy during photosynthesis. The experiments allowed researchers to understand at what temperature the plants thrived or were stressed.

“It appears from the species that we looked at in Cockburn Sound, the one most at risk from rising temperatures was Zostera nigricaulis which is commonly known as eel grass,” Ms Said stated.

Halophila ovalis, a species found in temperate to tropical areas and commonly known as paddle weed, spoon grass or dugong grass, was most able to withstand the higher temperatures.

Other species tested were Amphibolis griffithii, Posidonia sinuosa (the most widespread species in Cockburn Sound), Posidonia australis and Amphibolis antarctica, which are larger plants than the other two species assessed.

The research team found a heatwave in Perth that produced temperatures between three and four degrees higher than average summer temperatures would be likely to have a negative impact on the larger species which are generally able to withstand pressures for a greater duration than smaller species, but once damaged take longer to recover.

Heatwaves are predicted to become more frequent and more intense under climate change. An extreme marine heatwave in 2010 and 2011 saw a large area of seagrass in Shark Bay destroyed.

“With increasing ocean temperatures and an increase in marine heatwave events, seagrass species living close to their thermal limits are at risk from rising temperatures. There is limited temperature threshold information for seagrass species, which is critical information and can forewarn both present and future vulnerability to ocean warming.”

“There are other researchers around the world looking at climate resilience, but we have been missing this key baseline data to look at the physiology of seagrasses and how they may respond to these climate scenarios.”

ECU School of Science Associate Professor Kathryn McMahon, who co-leads the research on seagrass resilience said the findings were significant.

“These findings are really exciting as they indicate there are differences among seagrass species and population along our WA coast to ocean warming,” Associate Professor McMahon said.

“We can harness these differences and take actions to try and build resilience into our spectacular seagrass meadows.”