In the Wake of HMAS Diamantina – One Ten East log

We are about to go through immigration and throw off our lines at 3pm. Great sunny day here in Freo. Hope the weather holds! This is the second log from the voyage. Daily logs will be posted on the WAMSI website during the month long voyage

By Lynnath Beckley

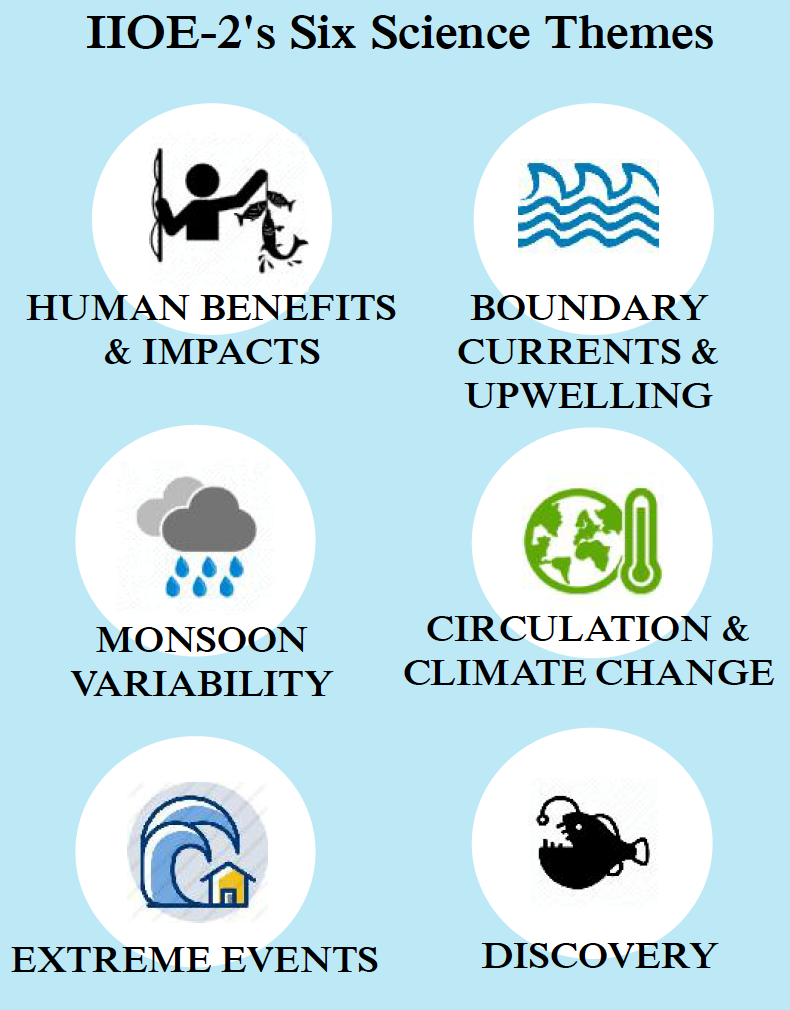

On 14th May 2019, the Research Vessel Investigator will depart Fremantle on an oceanographic voyage to the 110°E meridian in the south-east Indian Ocean. This voyage will be following in the wake of the HMAS Diamantina, which in the 1960s, took Australian scientists to study the physical, chemical and biological oceanography of the same region as part of the first International Indian Ocean Expedition. During the 2019 voyage, which is Australia’s major contribution to the second International Indian Ocean Expedition (IIOE-2), a multi-national team of scientists will repeat many of the measurements made nearly six decades ago to ascertain if there have been significant changes in the pelagic ecosystem near the western extent of Australia’s Exclusive Economic Zone.

|

|

The frigate HMAS Diamantina was the primary vessel used by Australian scientists during the first International Indian Ocean Expedition. Photo courtesy of the Queensland Maritime Museum. |

The HMAS Diamantina is the last remaining example of the British River Class frigates. Built in Australia and launched in 1944, the ship saw service in the latter part of World War 2 around Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Bougainville and Nauru before being paid off into the Reserve in August 1946. It was recommissioned in June 1959 as an Oceanographic Research Ship under the command of Lieutenant Commander Bruce D Gordon RAN. The ship carried scientists from the CSIRO but also assisted the Australian Army survey team along the north-west Australia.

Although there is now a new HMAS Diamantina 2 (a Huon Class Minehunter) in the Australian fleet, the legacy of the original vessel lives on as a popular exhibit in the Queensland Maritime Museum in Brisbane. Furthermore, her name is immortalised in hydrography with one of the deepest areas in the Indian Ocean, the Diamantina Deep (around 8,000 m depth) in the Diamantina Fracture Zone some 1,100 km south-west of Fremantle named after the ship. On the RV Investigator voyage the connection with the Navy has been maintained with Captain Curt Jenner AM and Captain Micheline Jenner AM conducting research on underwater sound and whales for the Australian Defence Force. This voyage is supported by a grant of sea time on RV Investigator from the CSIRO Marine National Facility.

|

|

The original HMAS Diamantina, at her berth at the Queensland Maritime Museum in Brisbane. Photo courtesy of the Queensland Maritime Museum. |

|

|

Eeva Leinonen, Vice Chancellor of Murdoch University (right), doing the honours and raising the second International Indian Ocean Expedition flag aboard RV Investigator in the Port of Fremantle. Captain Adrian Koolhof and Prof. Lynnath Beckley observed the proceedings. Photo: Micheline Jenner. |

Be sure to follow the daily posts of our One Ten East Logs at IIOE 2 and WAMSI