Ocean Food Webs – One Ten East log

One Ten East Logs from the IIOE-2 voyage aboard RV Investigator will be posted on the WAMSI website during the month long voyage.

Today’s rousing trade winds were for perfect sailing across the Indian Ocean pond! If we hang up all the sheets, we’ll be there shortly Kiran and Satya!

– Captain Micheline Jenner

Log from One Ten East

The RV Investigator is currently undertaking oceanographic research along the 110°E meridian off Western Australia as part of the second International Indian Ocean Expedition. The voyage is led by Professor Lynnath Beckley of Murdoch University and the research is supported by a grant of sea time on RV Investigator from the CSIRO Marine National Facility.

| Date: June 02, 2019 | Time: 1200 AWST |

| Latitude: 15.5°S | Longitude: 110°E |

| Wind direction: E | Wind speed: 17 knots |

| Swell direction: SE 2m, NE 0.5m, SW 2m | Depth: 5727 m |

| Air temperature: 27°C | Sea temperature: 27°C |

| Notes: At Station 17 of 20 on the 110°East line, we are in some of the deepest water so far. | |

Ocean Food Webs

By Prof Michael Landry

Food webs describe the feeding (trophic) relationships that exist among organisms in an ecosystem. If you have heard the old fisherman’s adage that “big bait catches big fish”, you may intuitively understand how ocean food webs operate, mainly on the basis of size, with larger consumers eating successively smaller prey down to where it all begins with microscopic phytoplankton. This is fundamentally different than food webs on land, where the plants are often much larger than their consumers (e.g., insects grazing on trees).

A further twist of ocean food webs is that different ocean conditions select for different sizes of phytoplankton. In the poorest (oligotrophic) environments, which occur over much of the tropical and subtropical open ocean, very small phytoplankton (photosynthetic bacteria) dominate because they are the most efficient competitors for nutrient uptake at low concentrations. In nutrient-rich coastal systems, large phytoplankton are dominant. One consequence of this difference is that open-ocean food webs lose most of their energy in transfers from tiny producers to tiny consumers on up, with little remaining in the end to support fisheries. In contrast, richer systems with large phytoplankton and larger consumers have fewer steps of intermediate consumers and can channel productivity more efficiently to fishes.

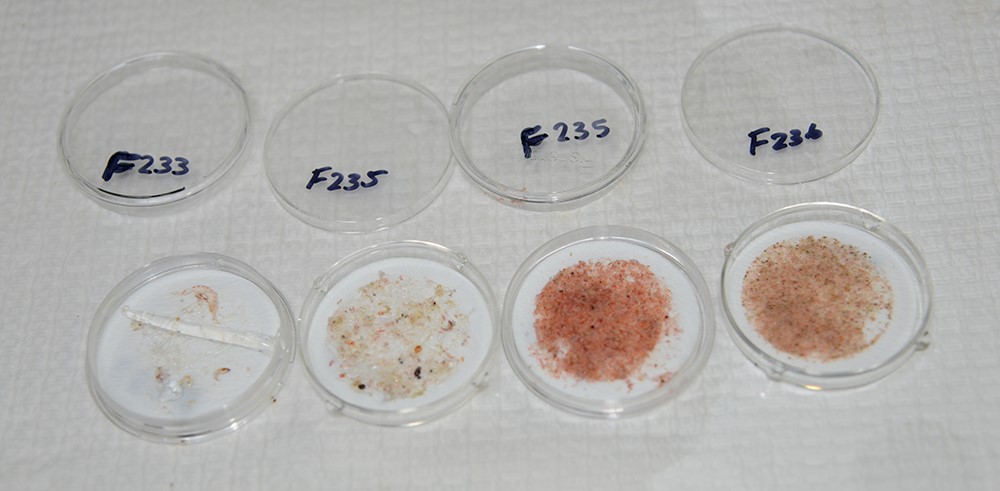

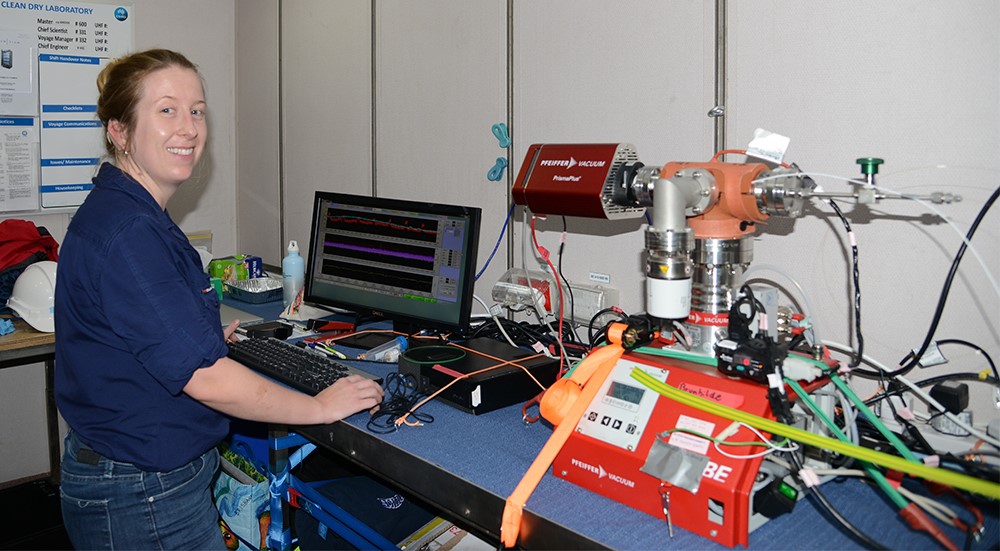

In this project (IN2019_V03), we are taking two approaches to compare food-web relationships along the stations and regions on the cruise track. One is experimental, involving measurements of community composition, productivity and grazing rates. The other utilizes information that resides in the isotopic composition of planktonic consumers to quantify their mean trophic positions in the food web relative to phytoplankton.

|

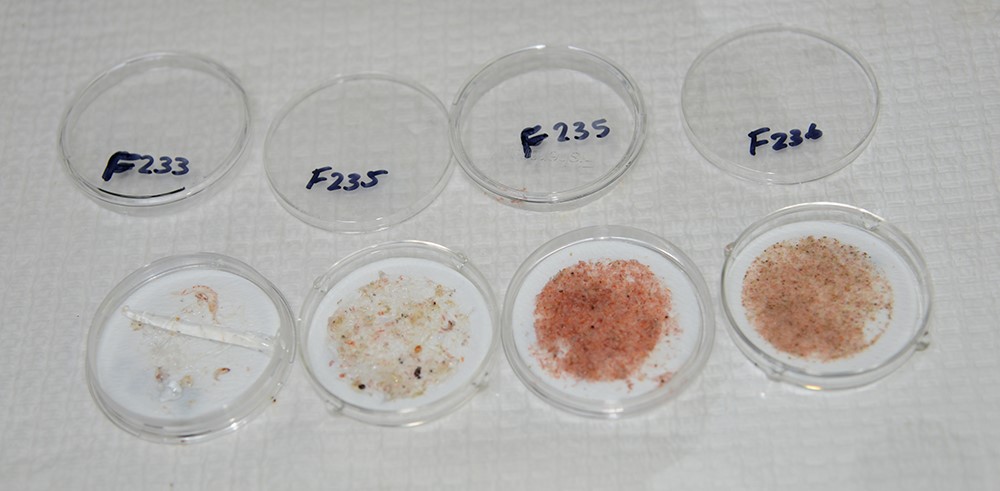

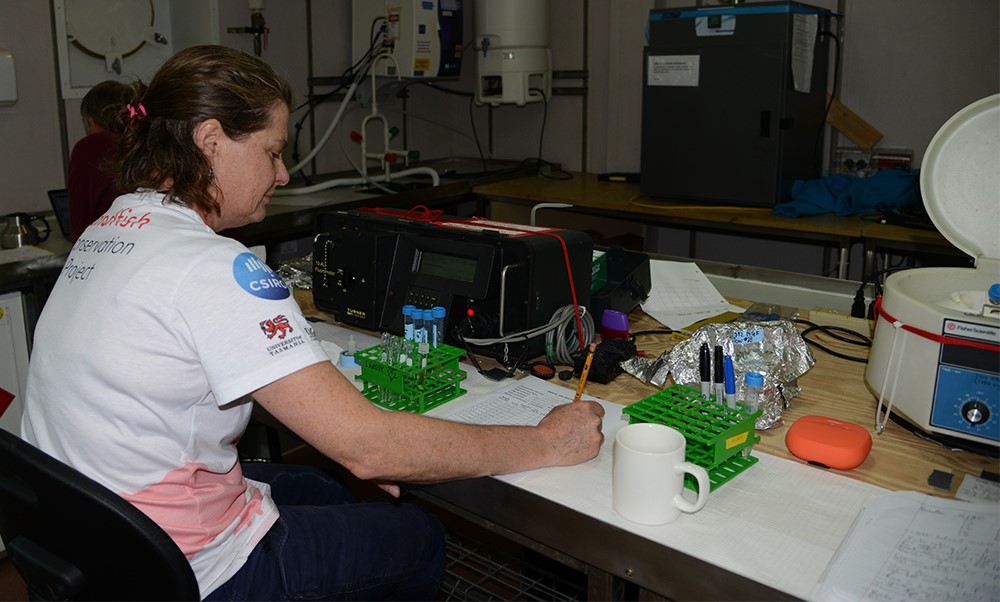

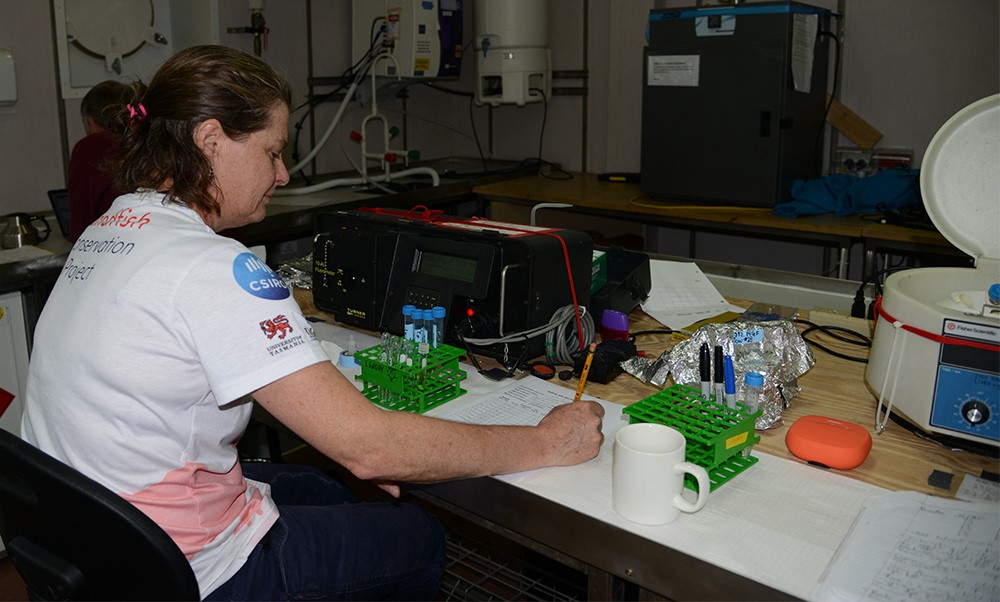

| Claire Davies (IMOS/CSIRO) halves one of the filtered zooplankton samples for sonification and fluorometric analysis to ascertain grazing by copepods. Photo: Micheline Jenner AM. |

|

| Prof Raleigh Hood (University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science) shows the copepod material which was macerated with the sonicator (a low frequency sound emitted from the metal spike, in backgorund) prior to determination of the chlorophyll content. Photo: Micheline Jenner AM. |

|

| Claire Davies (IMOS/CSIRO) measures the chlorophyll content with the fluorometer to determine the extent of grazing on phytoplankton by copepods in the mesozooplankton samples collected with the oblique plankton tow. Photo: Micheline Jenner AM.

|

Be sure to follow our daily Log from One Ten East at https://iioe-2.incois.gov.in or www.wamsi.org.au