Kimberley Indigenous rangers and marine scientists met last week (Tuesday 1st – Thursday 3rd December 2020) at the annual Indigenous Saltwater Advisory Group (ISWAG) forum in Broome.

ISWAG is an Indigenous-led and facilitated saltwater forum for the Kimberley. It includes members from nine saltwater Prescribed Native Title Body Corporates (PBC’s); Balanggarra, Wunambal Gaambera, Dambimangari, Mayala, Bardi Jawi, Nyul Nyul, Yawuru, Karajarri and Nyangumarta, which represents traditional owner groups across 90% of the Kimberley coastline. ISWAG was created to support Kimberley saltwater managers to implement their Healthy Country Plans through collaborative research, policy and management.

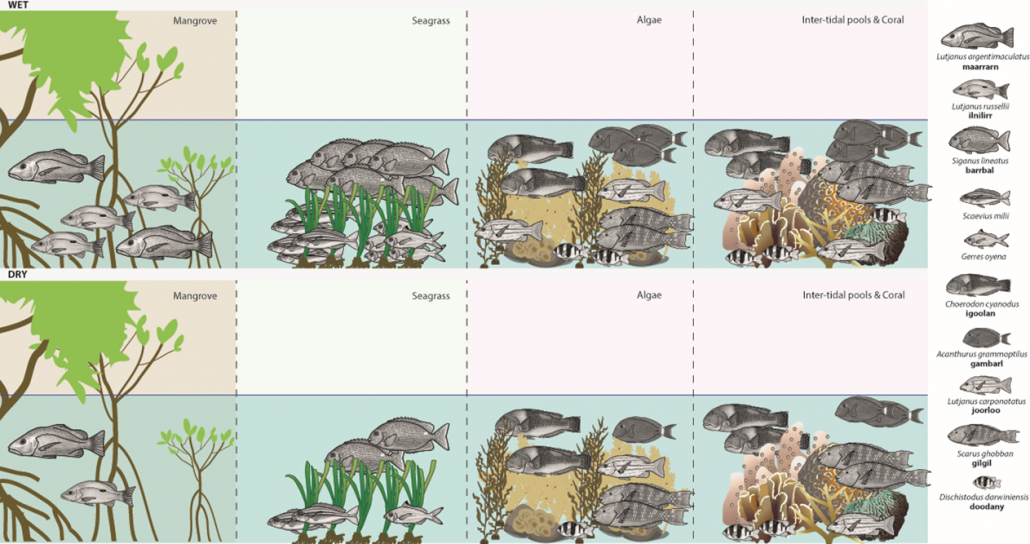

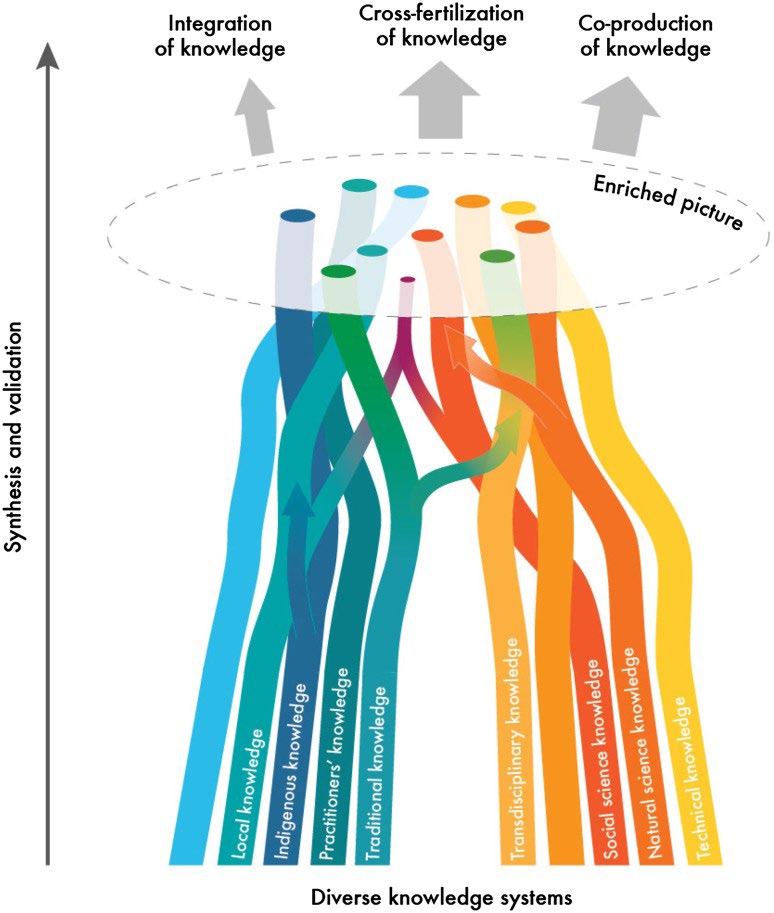

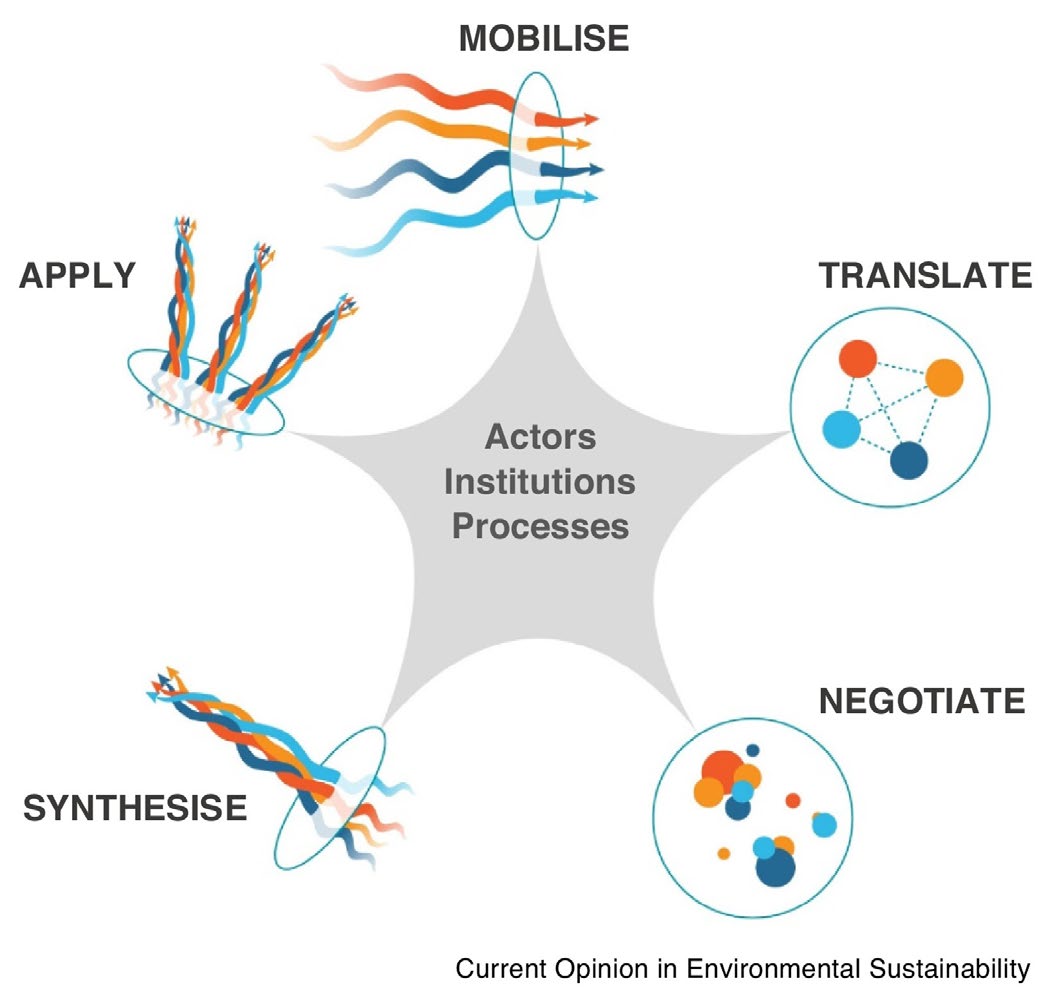

Throughout the three-day forum, the group shared Indigenous knowledge and pair it with cutting edge science to enable best practice saltwater management to ensure the long-term sustainability of marine species in the Kimberley. The forum is recognised by scientists from state and federal agencies and institutions as a key advisory body about saltwater knowledge and management issues across the Kimberley.

A key outcome from the 2020 forum, was the tabling of an Indigenous led 10-year turtle and dugong management plan for the entire Kimberley region. The plan, funded by Parks Australia and the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (DBCA), lays out the framework for an integrated western and traditional research approach to all aspects of turtle and dugong management and conservation in the region. It builds on decades of foundational work done by Indigenous and non-Indigenous marine scientists and managers towards the long-term sustainability of dugong and turtle populations in north west Australia.

At the forum, western science partners from the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS), DBCA, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) and Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development (DPIRD) specialising in turtle, dugong, fish and saltwater habitats, co-presented the results of recent marine science projects.

The Western Australian Marine Science Institution (WAMSI) also presented preliminary findings from a review of the processes and protocols for scientists working on saltwater country developed with ISWAG.

__________________________________________________________

Wunambal Gaambera Aboriginal Corporation (WGAC)

Desmond Williams, Uunguu Ranger, (WGAC), explains what they are doing on Wunambal Gaambera saltwater country to protect and monitor marine species.

“We went out on our wundaagu (saltwater) in a small plane to look at the turtle tracks from flatback turtles and hawksbill turtles, and we share the results with this ISWAG group to get a better understanding of what turtles are doing across the whole Kimberley.”

“We also did a survey of the marine threats such as fishing line debris, ghost nets and also look at where they are laying eggs and some of the threats, we have like dingoes eating the eggs on some of our islands.”

“This group is really helpful. We need to build our skills to manage our wundaagu. We get to learn a lot from the other ranger groups and scientists. It is really good for us Wunambal Gaambera people to be sharing our knowledge on the same level as the other ranger groups in the Kimberley.”

For Wunambal Gaambera people, mangguru (marine turtles) and balguja (dugong) are important cultural foods especially for cultural gatherings.

“We have hunted mangguru and balguja for generations and they are part of some people’s dreaming.

We know when a turtle is healthy by the shoulder fat. Our old people used to travel a long way by raft or canoe to outer islands to collect Amiya (turtle eggs) and survived on Amiya when they had no water.”

Nyamba Buru Yawuru (NBY)

Dean Mathews, Senior Project Officer, NBY, talks passionately about managing turtles and dugong on Yawuru Nagulagun Buru (Yawuru Sea Country) and why it is important to protect turtles on Yawuru country.

“If we are talking about the well-being of Roebuck Bay, protecting turtles and dugongs is very high on the priority for Yawuru people because of what those resources have provided for us for thousands of generations and we want to ensure the next generation have that to enjoy. It is a fundamental part of who we are,” explained Dean.

“A lot of our turtles for example the green turtle, do not have nesting sites here.

“Our rookeries (or nesting sites) are under a lot of pressure due to climate change, fishing, sea nets, plastics and hunting and so, as country managers we have to look at how the rookeries are sustaining them and what we need to do to look at the hunting aspects and frequency of take to protect our rookeries for future generations to enjoy.”

“Working collaboratively, we are all accountable and we, the Traditional Owners who have lived on and interacted with turtles and dugongs for many generations, want to be a part of the higher-level conversation and policy at the Commonwealth level in regard to planning and managing these species. ISWAG provides this opportunity for a united voice from Kimberley Ranger groups.”

Bardi and Jawi Niimidiman Aboriginal Corporation

Kevin George, Senior Cultural Advisor, Bardi Jawi Rangers spoke about the value of coming together.

“We have a duty of care and obligations and one of the major reasons we come together is to protect cultural customs, traditions, livelihoods, the whole works.”

DBCA

Dr Scott Whiting, Principal Research Scientist, DBCA said:

“Collaborative work is extremely important for long term conservation, especially for long lived animals with complex life cycles like turtles and dugongs.

Each group of Traditional Owners, managers, scientists and policy makers bring different skills, knowledge and impact to conservation outcomes. Collaboration is the only way for long-term management.”

Western Australian Marine Science Institution (WAMSI)

Dr Kelly Waples, Kimberley Marine Research Program Science Coordinator, (WAMSI), presented preliminary findings from a review of the process and protocols for scientists working on saltwater country developed with ISWAG.

The review is based on surveys with researchers, Healthy Country managers, Indigenous organisational staff, Traditional Owners and government staff who have worked through the steps outlined in the Collaborative research on Kimberley Saltwater Country – Guide for Researchers.

“The Kimberley is leading the way in encouraging western scientists to consider how they can collaborate with Indigenous rangers to address important outcomes for Healthy Country Plans,” Dr Waples said.

“This review will give ISWAG a better idea of how the process is working for the saltwater groups, researchers and government agencies so that ISWAG can consider any improvements that could lead to better results for the Kimberley.”

Acknowledgements

The forum was made possible through the contributions of all ISWAG parent PBCs and funding from the Kimberley Land Council, AIMS, Nyangumarta Warrarn Aboriginal Corporation, WAMSI, the National Environmental Science Program’s Marine Biodiversity Hub, DPIRD and DBCA.

Category:

Kimberley Marine Research Program