Using Gas to Grow – One Ten East Log

One Ten East Logs from the IIOE-2 voyage aboard RV Investigator will be posted on the WAMSI website during the month long voyage.

Log from One Ten East

The RV Investigator is currently undertaking oceanographic research along the 110°E meridian off Western Australia as part of the second International Indian Ocean Expedition. The voyage is led by Professor Lynnath Beckley of Murdoch University and the research is supported by a grant of sea time on RV Investigator from the CSIRO Marine National Facility.

| Date: May 26, 2019 | Time: 1200 AWST |

| Latitude: 26°S | Longitude: 110°E |

| Wind direction: SSE | Wind speed: 18 knots |

| Swell direction: SSW | Depth: 3988 m |

| Air temperature: 22.6°C | Sea temperature: 23.8°C |

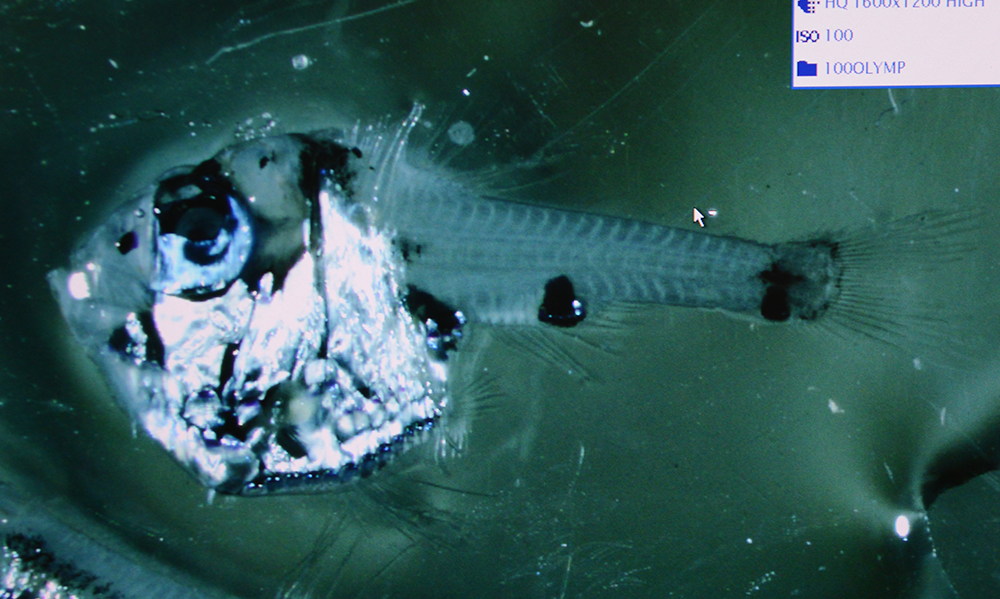

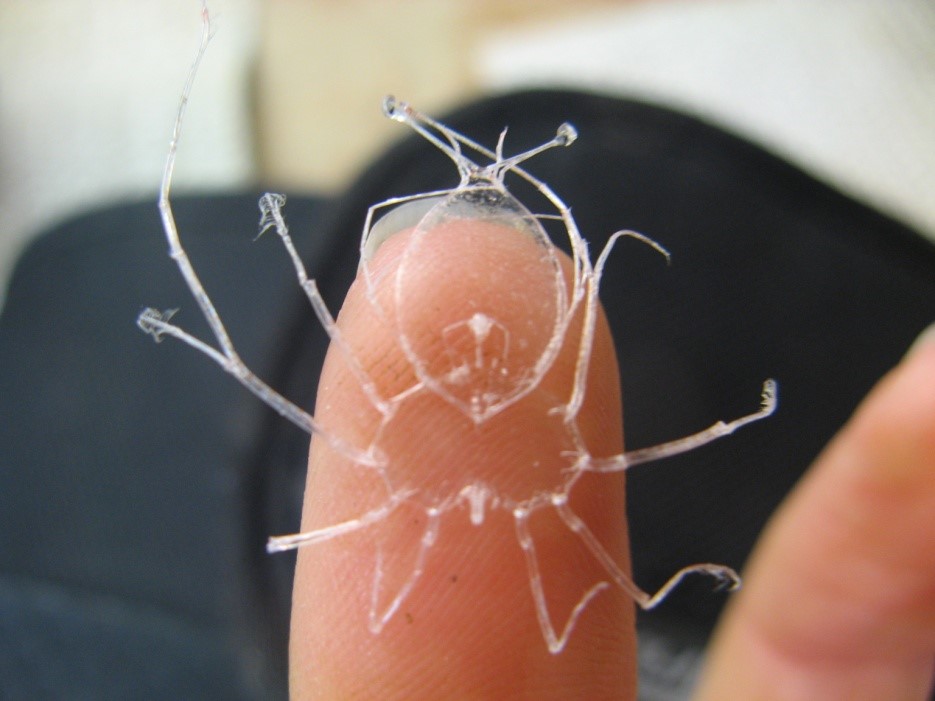

Notes: There is a clear influence of the Leeuwin Current on the samples being collected with more tropical species appearing in the plankton nets and the seabirds sighted.

Using Gas to Grow

By Dr Eric Raes

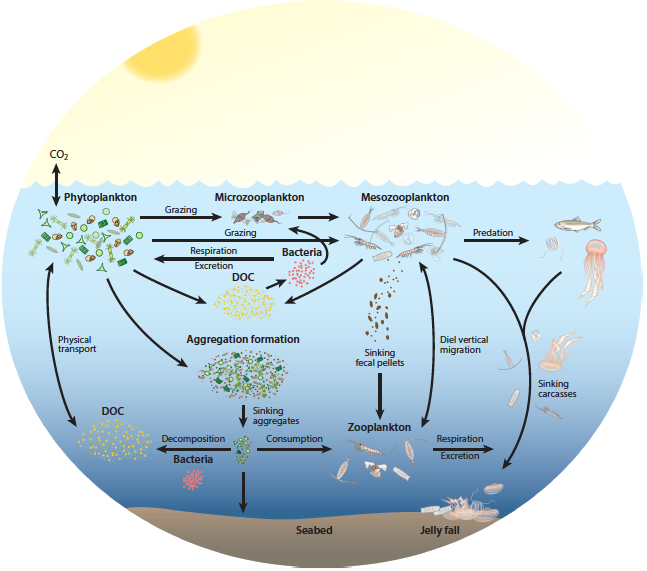

During this voyage we are focusing our research efforts on nitrogen in particular, as this element is essential for all life forms on Earth. On land, we are accustomed to adding nitrogen as a fertiliser to increase the growth and yield of our crops. As on land, in the sea, nitrogen is a vital nutrient for the growth of microscopic organisms. On this voyage, we are examining the different ways nitrogen is used by the microbes and phytoplankton, which supply us with the oxygen that we breathe.

One of our questions is to determine how much energy from the sun is captured by the phytoplankton and how the availability of nitrogen controls their growth. Another question targets a special group of microscopic life, the nitrogen gas fixers! These microorganisms are able to use the nitrogen gas from the atmosphere (which is roughly 80% nitrogen gas and 20% oxygen). Although most organisms use oxygen, only a select few can actually use nitrogen.

In agriculture, we have long known about the beneficial effects of microorganisms that use nitrogen gas such as Rhizobium in the root nodules of peas and beans. In the ocean, however, the beneficial effects of using nitrogen gas as an energy source for growth are less well understood. During our voyage we have set up experiments to measure just how much nitrogen gas the microorganisms are using. The results from these experiments will give us a better understanding how much food (in fact, energy for fishes), is available in the south-east Indian Ocean and what might happen in the future.

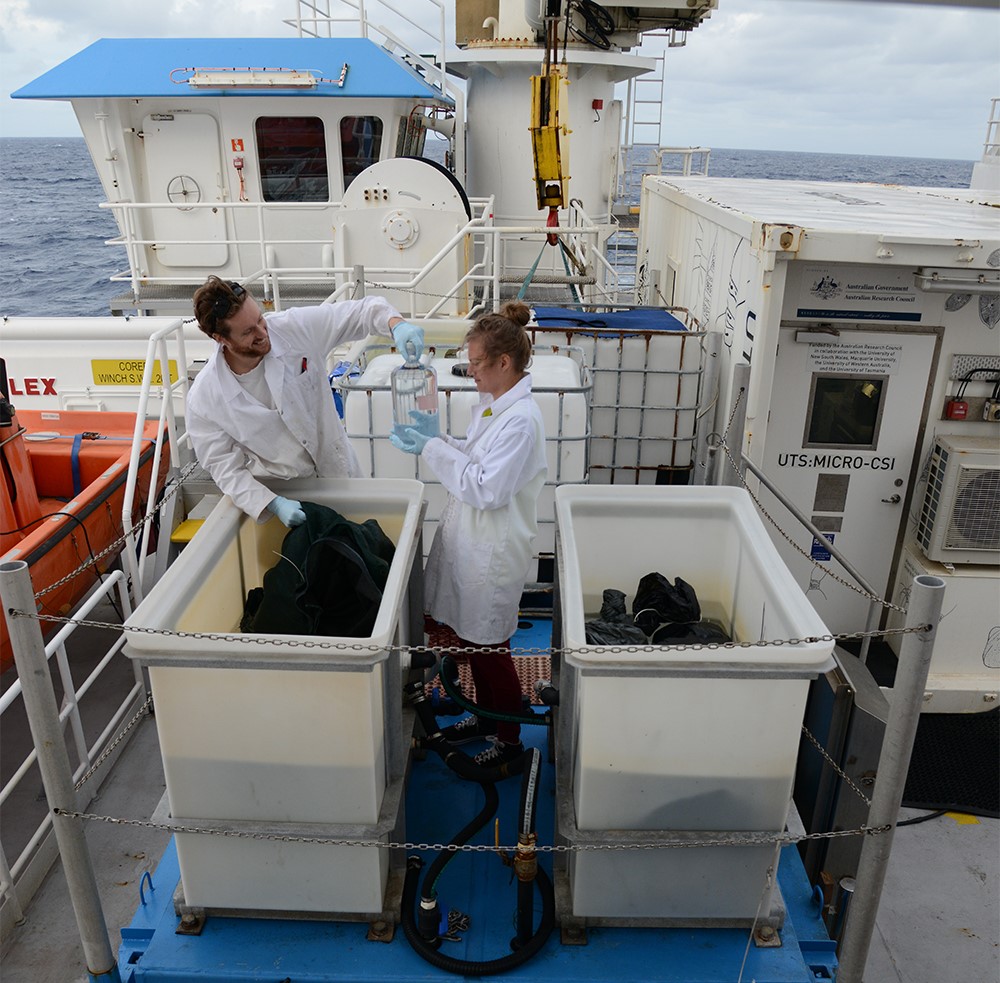

Dr Eric Raes (CSIRO) with Cora Horstmann (PhD student at the Alfred Wagener Institute in Germany) tending their experiments in the through-flow seawater incubators on board the RV Investigator. Photo: Micheline Jenner AM

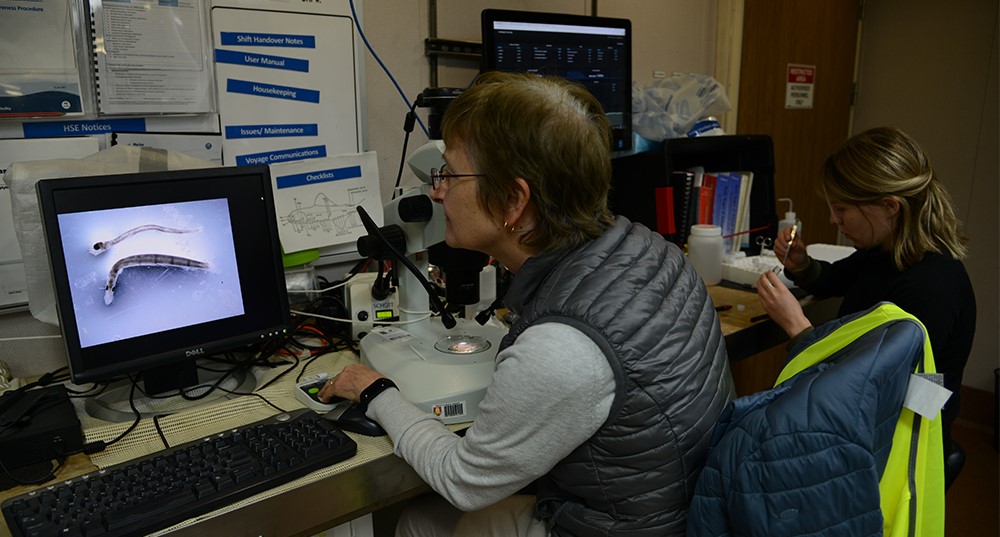

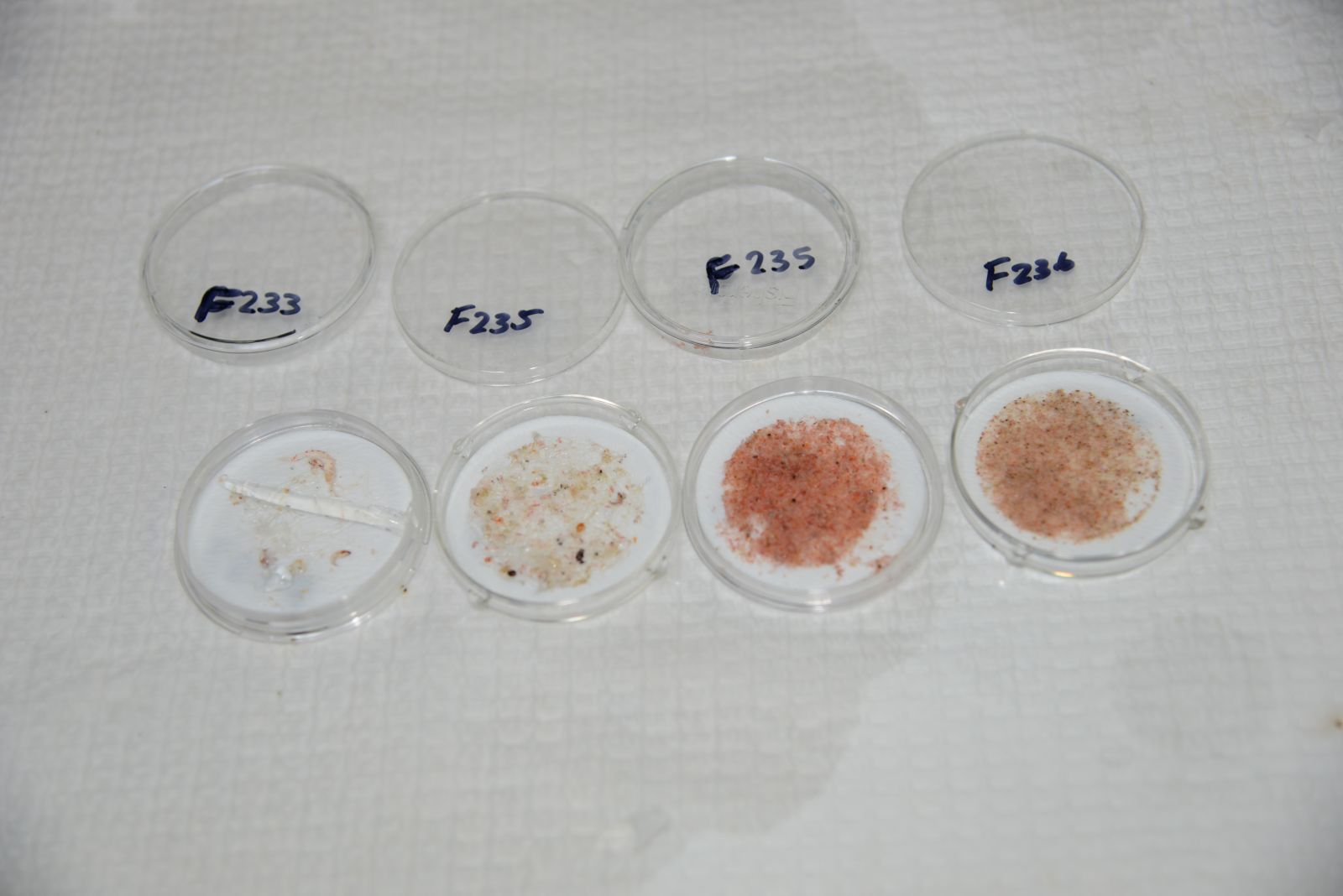

Dr Eric Raes (CSIRO) with Cora Horstmann (PhD student at the Alfred Wagener Institute in Germany) examining their incubated samples for their nitrogen-uptake experiments on board the RV Investigator. Photo: Micheline Jenner AM.

The blue light the modular Isotope Laboratory aboard the RV Investigator, Cora Horstmann (PhD student at the Alfred Wagener Institute in Germany) prepares for nitrogen uptake experiments with Dr Eric Raes (CSIRO). Photo: Micheline Jenner AM.

Be sure to follow our daily Log from One Ten East at https://iioe-2.incois.gov.in or www.wamsi.org.au.