Drifters and Floaters – One Ten East log

One Ten East Logs from the IIOE-2 voyage aboard RV Investigator will be posted on the WAMSI website during the month long voyage.

Log from One Ten East

The RV Investigator is currently undertaking oceanographic research along the 110°E meridian off Western Australia as part of the second International Indian Ocean Expedition. The voyage is led by Professor Lynnath Beckley of Murdoch University and the research is supported by a grant of sea time on RV Investigator from the CSIRO Marine National Facility.

| Date: June 10, 2019 | Time: 1200 AWST |

| Latitude: 22°S | Longitude: 112°E |

| Wind direction: SW | Wind speed: 14 knots |

| Swell direction: SW 4-5 m | Depth: 4946 m |

| Air temperature: 22°C | Sea temperature: 25°C |

| Notes: Currently planning to tow the Triaxus for section 3, in a beautiful rolling swell. |

Drifters and Floaters

By Joel Cabrié and Prof Lynnath Beckley

During voyage IN2019_V03 we have deployed 14 weather buoys in the south-east Indian Ocean for the Australian Bureau of Meteorology and the American National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Meteorological drifting buoys are autonomous platforms that are typically deployed from ships to collect and report basic meteorological measurements. These platforms, as the name implies, drift with the near-surface currents to help fill otherwise data-sparse areas. The style of drifting buoy that is deployed by most meteorological and oceanographic agencies is a spherical buoy (SVP) fitted with a holey-sock drogue that forces the buoy to follow the path of currents near the surface, from which an estimate of the Lagrangian current can be deduced. The Bureau of Meteorology use an SVP-B buoy which measures atmospheric pressure in addition to sea surface temperature and Lagrangian current. A SVP-B buoy is distinguishable from an SVP buoy by a small stub mast on top of the buoy that houses the pressure port.

The main deployment areas for the Bureau of Meteorology are the Indian and Southern Oceans to maximise the benefit to the Bureau’s operations, whilst the Tasman Sea benefits from buoys deployed by MetService, New Zealand. The Bureau currently maintains a fleet of between 25-30 buoys in the Indian and Southern Oceans as part of their contribution to the international drifting buoy program of around 1,450 buoys.

Prior to deployment, on the aft deck of RV Investigator, Dr Jessica Benthuysen (AIMS) holds the drogue, while Maxime Marin (PhD student University of Tasmania) holds the floating buoy of this drifter. Photo: Micheline Jenner AM.

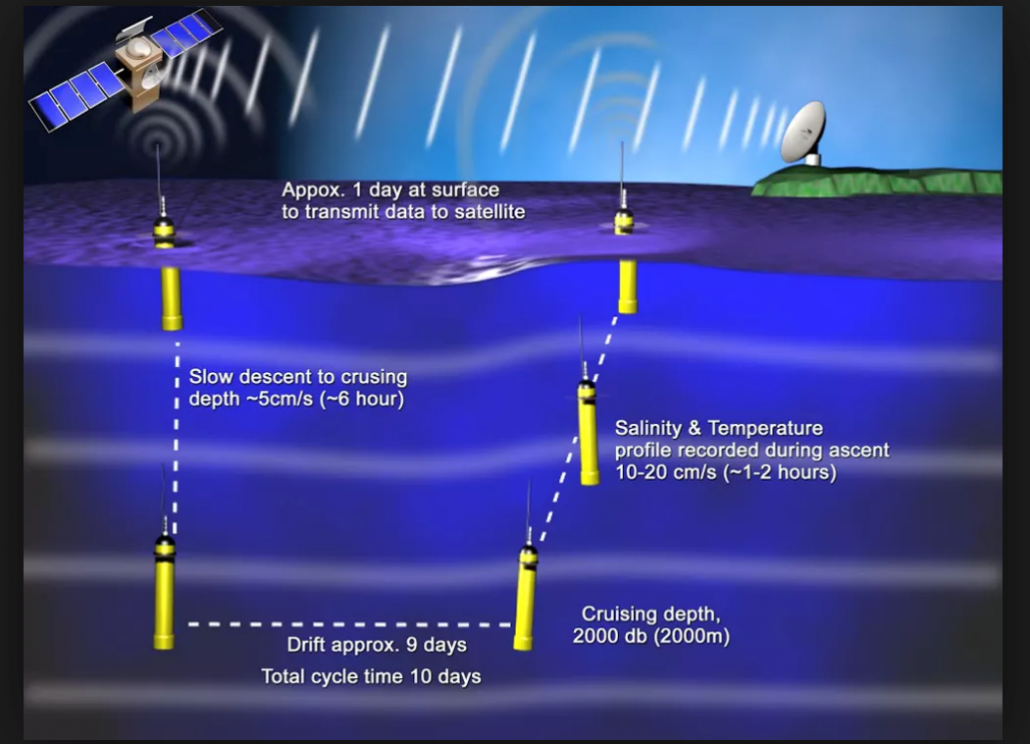

On our 110° East voyage we have also deployed an ARGO float for Australia’s Integrated Marine Observing System (IMOS). These robotic floats have revolutionized oceanography as they are capable of autonomously measuring the temperature and salinity profile in the ocean down to 2,000 m and transmitting this information back to base by satellite each time the float returns to the surface. There is a large international fleet of nearly 4,000 floats operating globally in all oceans providing vital information to oceanographers who monitor and model our blue planet. http://imos.org.au/facilities/argo/.

This schematic diagram shows the passage of an ARGO float as it progresses through its 10-day data collection cycle. Source: IMOS.

During our voyage we have also assisted our Japanese colleagues at the JAMSTEC agency in Tokyo by deploying two APEX deep ARGO floats for them. Remarkably, these round glass floats can monitor the deep ocean down to 6,000 m. However, just getting them to the RV Investigator was a complicated process as they had to be air-freighted from Tokyo to Sydney and then they crossed the Nullarbor on the back of a truck, making it to the Port of Fremantle just in time to be loaded on the RV Investigator! The first results from these floats are available at www.jamstec.go.jp/ARGO/argo_web/argo/?page_id=31&lang=en.