By : Matthew Fraser, University of Western Australia; Ana Sequeira, University of Western Australia; Brendan Paul Burns, UNSW; Diana Walker, University of Western Australia; Jon C. Day, James Cook University, and Scott Heron, James Cook University

The devastating bleaching on the Great Barrier Reef in 2016 and 2017 rightly captured the world’s attention. But what’s less widely known is that another World Heritage-listed marine ecosystem in Australia, Shark Bay, was also recently devastated by extreme temperatures, when a brutal marine heatwave struck off Western Australia in 2011.

A 2018 workshop convened by the Shark Bay World Heritage Advisory Committee classified Shark Bay as being in the highest category of vulnerability to future climate change. And yet relatively little media attention and research funding has been paid to this World Heritage Site that is on the precipice.

Shark Bay, in WA’s Gascoyne region, is one of 49 marine World Heritage Sites globally, but one of only four of these sites that meets all four natural criteria for World Heritage listing. The marine ecosystem supports the local economy through tourism and fisheries benefits.

Around 100,000 tourists visit Shark Bay each year to interact with turtles, dugongs and dolphins, or to visit the world’s most extensive population of stromatolites – stump-shaped colonies of microbes that date back billions of years, almost to the dawn of life on Earth.

Commercial and recreational fishing is also extremely important for the local economy. The combined Shark Bay invertebrate fishery (crabs, prawns and scallops) is the second most valuable commercial fishery in Western Australia.

Under threat

However, this iconic and valuable marine ecosystem is under serious threat. Shark Bay is especially vulnerable to future climate change, given that the temperate seagrass that underpins the entire ecosystem is already living at the upper edge of its tolerable temperature range. These seagrasses provide vital habitat for fish and marine mammals, and help the stromatolites survive by regulating the water salinity.

Stromatolites are a living window to the past. Matthew Fraser

Shark Bay received the highest rating of vulnerability using the recently developed Climate Change Vulnerability Index, created to provide a method for assessing climate change impacts across all World Heritage Sites.

In particular, extreme marine heat events were classified as very likely and predicted to have catastrophic consequences in Shark Bay. By contrast, the capacity to adapt to marine heat events was rated very low, showing the challenges Shark Bay faces in the coming decades.

The region is also threatened by increasingly frequent and intense storms, and warming air temperatures.

To understand the potential impacts of climatic change on Shark Bay, we can look back to the effects of the most recent marine heatwave in the area. In 2011 Shark Bay was hit by a catastrophic marine heatwave that destroyed 900 square kilometres of seagrass – 36% of the total coverage.

This in turn harmed endangered species such as turtles, contributed to the temporary closure of the commercial crab and scallop fisheries, and released between 2 million and 9 million tonnes of carbon dioxide – equivalent to the annual emissions from 800,000 homes.

Read more: Climate change threatens Western Australia’s iconic Shark Bay

Some aspects of Shark Bay’s ecosystem have never been the same since. Many areas previously covered with large, temperate seagrasses are now bare, or have been colonised by small, tropical seagrasses, which do not provide the same habitat for animals. This mirrors the transition seen on bleached coral reefs, which are taken over by turf algae. We may be witnessing the beginning of Shark Bay’s transition from a sub-tropical to a tropical marine ecosystem.

This shift would jeopardise Shark Bay’s World Heritage values. Although stromatolites have survived for almost the entire history of life on Earth, they are still vulnerable to rapid environmental change. Monitoring changes in the microbial makeup of these communities could even serve as a canary in the coalmine for global ecosystem changes.

The neglected bay?

Despite Shark Bay’s significance, and the seriousness of the threats it faces, it has received less media and funding attention than many other high-profile Australian ecosystems. Since 2011, the Australian Research Council has funded 115 research projects on the Great Barrier Reef, and just nine for Shark Bay.

Coral reefs rightly receive a lot of attention, particularly given the growing appreciation that climate change threatens the Great Barrier Reef and other corals around the world.

The World Heritage Committee has recognised that local efforts alone are no longer enough to save coral reefs, but this logic can be extended to other vulnerable marine ecosystems – including the World Heritage values of Shark Bay.

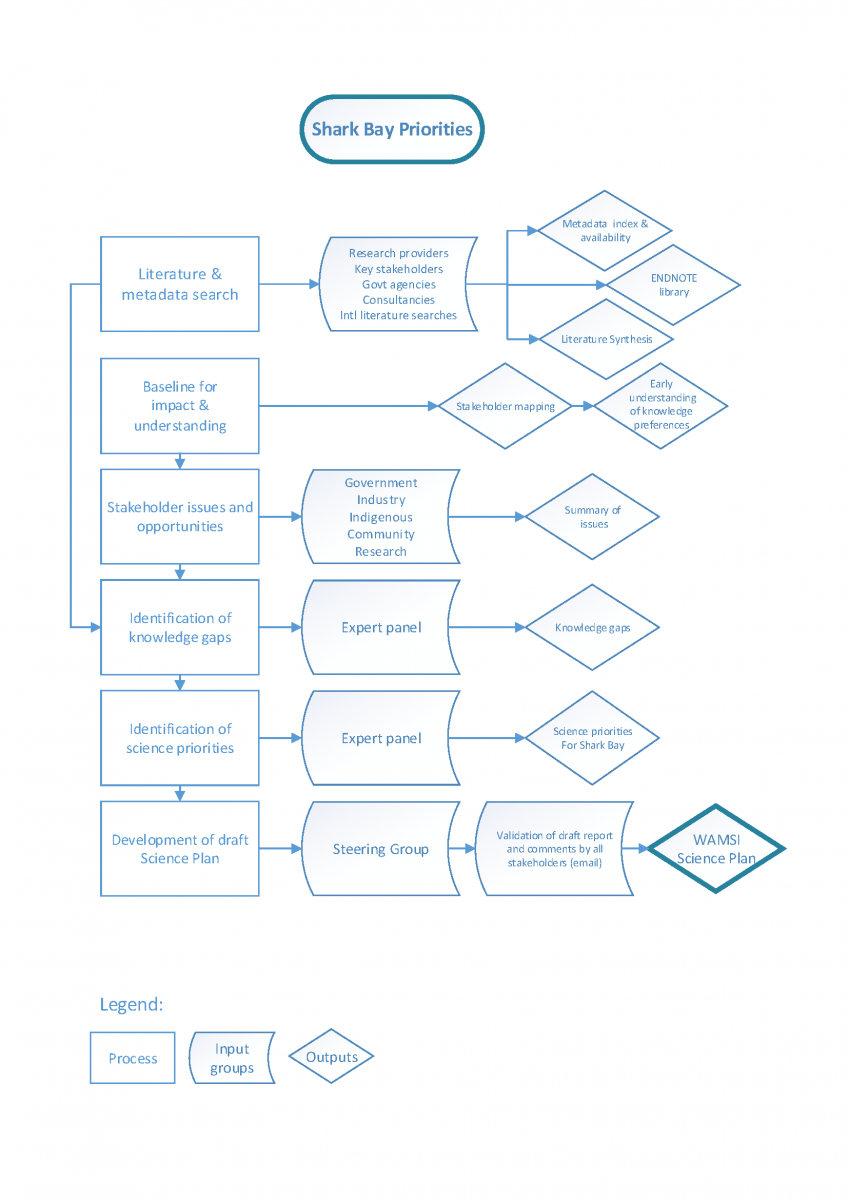

Safeguarding Shark Bay from climate change requires a coordinated research and management effort from government, local industry, academic institutions, not-for-profits and local Indigenous groups – before any irreversible ecosystem tipping points are reached. The need for such a strategic effort was obvious as long ago as the 2011 heatwave, but it hasn’t happened yet.

Read more: Marine heatwaves are getting hotter, lasting longer and doing more damage

Due to the significant Aboriginal heritage in Shark Bay, including three language groups (Malgana, Nhanda and Yingkarta), it will be vital to incorporate Indigenous knowledge, so as to understand the potential social impacts.

And of course, any on-the-ground actions to protect Shark Bay need to be accompanied by dramatic reductions in greenhouse emissions. Without this, Shark Bay will be one of the many marine ecosystems to fundamentally change within our lifetimes.

Matthew Fraser, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, University of Western Australia; Ana Sequeira, ARC DECRA Fellow, University of Western Australia; Brendan Paul Burns, Senior Lecturer, UNSW; Diana Walker, Emeritus Professor, University of Western Australia; Jon C. Day, PSM, Post-career PhD candidate, ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, James Cook University, and Scott Heron, Senior Lecturer, James Cook University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

A large number of lead scientists (35), both local and international have been formally approached to contribute to the project by providing publications and metadata of their Shark Bay research.

A large number of lead scientists (35), both local and international have been formally approached to contribute to the project by providing publications and metadata of their Shark Bay research.